In May 2017 I had the pleasure of attending the Music Encoding Initiative’s conference in Tours, France. Such a passionate, knowledgeable, multi-talented group of people, eager to share information about music technologies and information! The focus of this organization is on a particular digital format for musical scores, which is also called MEI, and I want to write today about the possibilities of using MEI to make new kinds of critical editions and music transcriptions. I can’t claim much of this content as my own; mostly I am just summarizing what other people—my web developer husband, the leaders of the MEI initiative, Joachim Veit in a keynote speech at the conference, and others—have taught me. I am so grateful to all of them for helping me to learn about this technological advance that is so useful for my work but overwhelms me to try to understand on my own.

So, MEI is a markup language. What is a markup language? We are talking about a language of terms and symbols that are used to give information about a separate text (a written text, a musical score, or a visual image). The classic example is HTML, which most people have used or at least seen. Think about HTML: even someone who knows nothing about computer coding can see that it contains the text of something like a webpage and files for graphics and other images with notes that say things like “this text is bold” or “this text is in this certain font and size” or “this text starts at this point on the page.” These notes are all examples of markups. So HTML programming is really just using an editing program to upload or write web content and then add notes at the appropriate points about how that content will look and maybe also how it will function (like a markup that makes certain text function as a link). MEI is this kind of language but developed especially for rendering musical scores, which are special kinds of texts. In that case, the “main text” are the musical notes. MEI is a type of XML (extensible markup language). As compared to HTML, XML is special in that it easily supports hierarchical structures because its basic unit is the “element,” which is then further described with tags that occupy a secondary position. A set of rules or schema in a kind of master file governs how the elements and tags can relate. XML is especially handy for music scores, because it can be used to easily organize symbols into the necessary hierarchies such as chord, measure, phrase, system/line of music, section, instrumental or vocal part, contrapuntal voices, or movement of a piece.

When people analyze music they often make use of hierarchical concepts such as motives or the designation structural versus elaborate/decorative notes. MEI is therefore great not just great for making musical scores but also making or rendering analyses of musical scores. Another point where MEI wins with me is that it is completely open source. There are renders that can read it, such as Verovio, or it can be converted into .sib or .xml so that something like Sibelius can read it. But one can also look directly at the marked up text, make changes to it, or search it. One can also make changes to schemata that govern the rules for MEI files. As MEI leaders proudly point out, the code of the files used in programs like Sibelius and Finale, while very useful, are “black boxes” of proprietary information that the user can only access through the program interface. What you can do is only as flexible as that interface allows. The people involved in the initiative tend to be academics who really want to make MEI better and better for the purposes of scholarly research and the needs of performers, without concern for making monetary profits. A scholar could write to Finale’s parent company about a change they really needed to have made to the Finale software for a certain research project, but Finale would probably not be interested unless that change also translated into a financial opportunity for them (which is fine—they are running a company for profit). The people developing MEI are much more open to such requests.

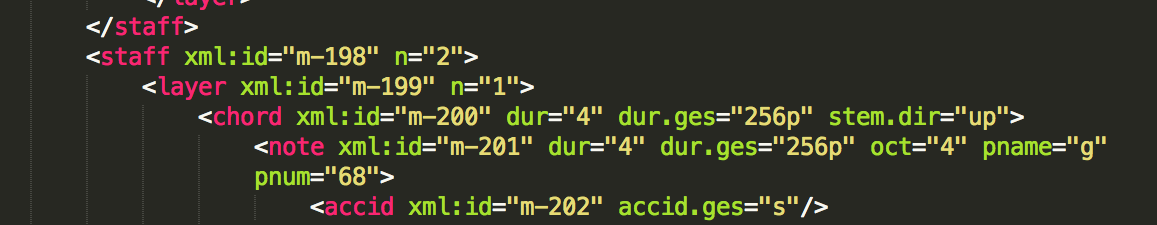

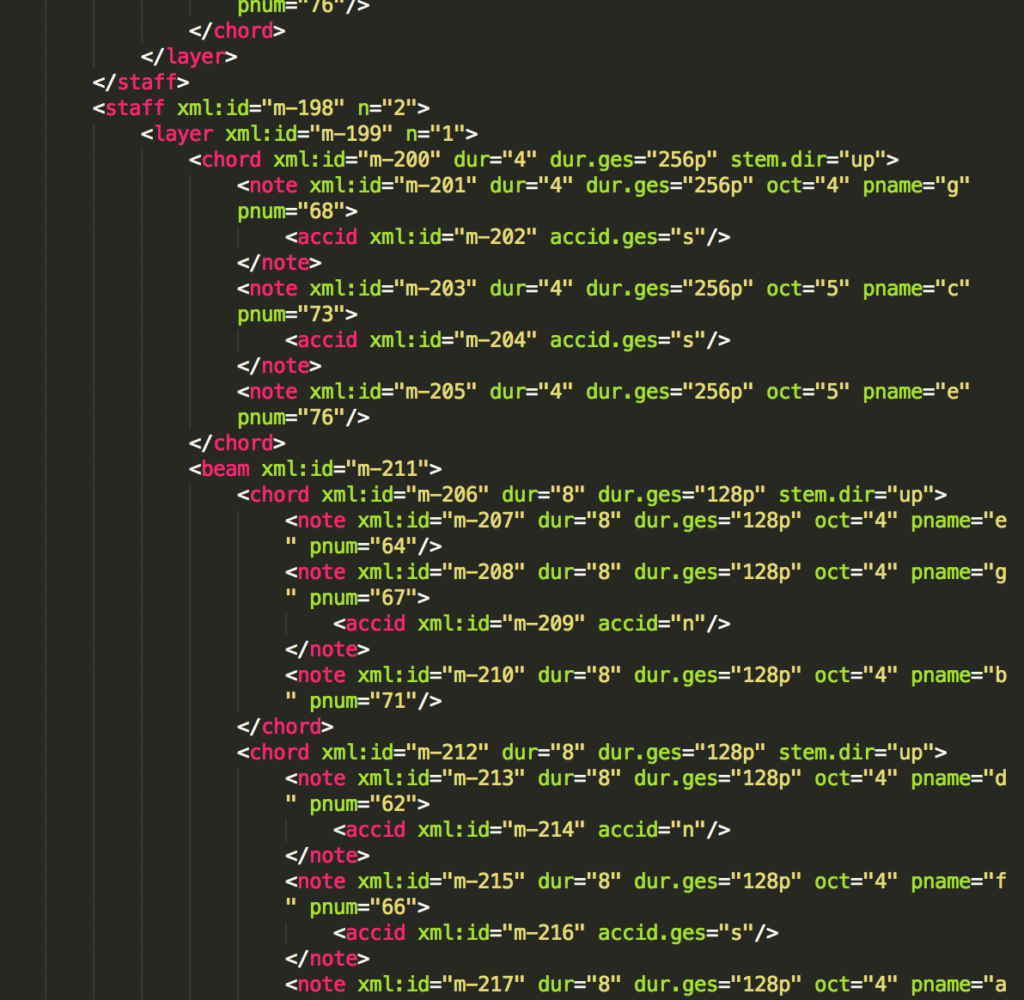

Here is a screenshot of a piece of music that I have been working with in MEI, Recuerdos by Gabriel Grovlez, as it appears in Sublime Text.

The hierarchical nature of the file type is clearly illustrated by its indented structure. I won’t go into much more detail about MEI. Those who are interested to know more can go to the official website for the Music Encoding Initiative here. What I am using MEI for at the moment is the analysis of scores such as this one, by working with my husband who is a computer programmer to write search programs. That subject is for a later post. Here, let’s see what Joachim Veit had to say about using MEI for critical editions and how his comments could be extended into the realm of music transcriptions.

Joachim Veit is a German musicologist who over the past 30 years has developed a reputation as an editor of critical editions, especially his editions of Carl Maria von Weber’s compositions. It is a testament to Veit’s expertness as an editor that he is open to using something like MEI, which is quite different from the pen-and-paper editing process that he was used to but that also offers many new advantages. On the final day of the Tours MEI conference, Joachim Veit gave a keynote speech about what he has been doing with MEI since 2012, under the auspices of the Edirom Project. Based on my notes, here were some of his main points about how MEI has helped him to make better critical editions.

First, MEI allows the critical edition to become less hierarchical and irreversible. Especially in situations where an editor is dealing with several versions of one composition or a type of musical symbol like a neume that we don’t have today and will require interpretation and translation into modern notation, editors have to decide on the singular, final version to be printed on the page. This decision is often not absolute but is a matter of picking the best of multiple, competitive options. In many cases the decision could have reasonably gone a different way. Critical editors typically discuss these decisions in the critical notes, but in book format those notes are in a separate section from the edited score. With MEI, Veit says that multiple versions can be encoded equally and then rendered as several possibilities placed at the same point in the digital score through the use of pop-up windows or something similar. Another possibility is attaching excerpts of the original manuscript at precise points in the score for clarifying sticky decisions, like a picture of the original symbol that has been translated into something else in the modern score.

In addition to increasing the information the critical edition can contain and organizing that information in a more accessible way, digital scores made with these markup tools also democratize decisions about the score, giving people besides the editor quick access to the primary source materials that permit them to make decisions alternative from those of the official editor. Similarly, Veit emphasized that a more collaborative approach to editing can be realized with layered markups. At this point, critical editions of many canonical works have already been attempted one time around and now a new generation of editors is making new attempts. What should they do with the old editions, though? Veit hopes that if editors switch to digital formats with markup tools, they can take someone else’s edition and then add their own markups to it as another layer. Because MEI is so well suited to hierarchical organization of information, such a thing could be elegantly done with it. One caveat Veit made here was that if this practice were to come into use, standards would need to be set so that digital editions didn’t become a mess of comments on top of comments—think about what happens currently in a lengthy Facebook comments thread. I think that on this point he sees where the democratization of the editing process needs to have meaningful limits, and that publishing professionals would still have roles to play in issues such as this one.

A final main point Veit put forward for consideration is that markup languages can allow us to consider an example of music notation “in all of its contextual specificity.” He gave us an example of what he meant, that of a specialized tremlo marking in a von Weber orchestral score. With markups we can go beyond just deciding which single marking to put in its place and give more specific information about how that tremlo would be played, through some kind of pop-up graphic, written explanation, or even an audio file that demonstrates it. And a further option, although I don’t remember Veit saying this explicitly, is that one could add “extramusical” details to a critical edition. As they were originally conceived, these critical editions focused on the sound dimensions of music, such as the notes to be played and the text to be uttered at specific points in time. If some of you are saying, “But wait, what are the dimensions of music besides sound—isn’t that all there is?”, then consider a genre in which music is part of creating a dramatic situation like opera, movies, or any kind of dramatic tradition you know of that incorporates music. In a digital critical edition the sonic elements could still be foregrounded, with any additional information appended in attributes. Or, one could radically reconceive the notion of a musical score for such genres and level the playing field among the various types of sensory information that make up the musical experience, even to the point of expanding the rules governing the markup in the schema file. Such a score could really function in interesting ways as analytical documentation of cultural phenomena.

Making critical editions used to be a primary activity of historical musicologists, but it’s not as common now. Part of the reason is that a lot of great critical editions of scores people care about have already been made, but I personally never had much interest in such work because it all seemed kind of…musty. Old-fashioned, dare I say. The possibilities in something like MEI seem to breathe new life into making critical editions. When I teach introductory classes about the musicology discipline in the future, I am definitely going to include what I have learned about MEI on the critical editions day. Although I can’t speak in the place of ethnomusicologists, it seems to me that something similar could be said for the potential of MEI to invigorate the practice of transcribing, because in both cases there are difficulties that stem from the limitations of the concept of text-as-artwork. In fact, the discomfort with this concept among historical musicologists largely grew from their exposure to the innovative research of ethnomusicologists about the nature of music. That is, we tend to understand something that is written down, especially if it looks very official and polished, as authoritative, and that is a problematic perception for anyone who is really thinking about how visual representations of music relate to the musical experience that it describes (in the case of a transcription) or prescribes (in the case of a musical score functioning as a set of instructions for performers). In both cases we sense the gap. In musicology we are in fact often using the score as a kind of descriptive transcription in order to analyze “real life” musical experiences in the past, and thus we end up facing many of the same issues as ethnomusicologists do regarding transcription.

Veit, in the keynote I am describing, referenced this problem with his constant emphasis on the “context” in which a certain musical score was made or was/is being used. While I am not too fond of the text/context heuristic, the point about how MEI can solve certain problems for music editors is still clear enough according to it. The text is singular but context is multiple; it can have infinitely many versions according to each performance situation and each one of those can involve infinitely many pieces. The text is static but contexts are dynamic. And so on. Among many musicologists currently there is, I think, a desire to go beyond textual analysis and into the analysis of “life itself” or “humans themselves”, but texts can seem so authoritative that whenever your analysis involves their use, it is easy to conform your perspective and method of analysis to them. This is an issue that ethnomusicologists have already been confronting in radical ways for decades. One has trouble choosing a single version of a certain sound in a transcription of a musical event, or describing a complex phenomenon with just one symbol. Like the text/context dichotomy, there can be a dissatisfying gap between transcription and “real life,” especially when a musical performance involves much more than the notes that can be pinpointed on a staff.

Both ethnomusicologists and musicologists are today searching for methods that capture the multiplicity and dynamism that we know to be true of music, not being forced to settle on one authoritative, static version or only one aspect of a musical experience and then cut out all the rest. This issue of the authority of the text also extends, as Veit noted, to a problem with giving too much authority to single people. The collaborative spark that gives birth to the musical texts we love can be retained, if only a little bit, in the collaborative, layered work that becomes possible for score edition with the MEI tools. I wonder if the same could be said for descriptive transcriptions. I know that the MEI community really does want people studying all different kinds of musical phenomena to try to use and develop the MEI framework. At the Tours conference I only saw one example of this, about ancient Chinese music, but because this musical system had a notational system, the issue here is not really transcription so much as translation from one score format into another. It would truly be exciting to see what ethnomusicologists as well as musicologists who work with notated compositions could do with MEI, as they are motivated to creatively solve the notational problems that arise concerning specific research questions and editorial perspectives.