During my very first visit to Pakistan, as a musicologist who loves music, I really wanted to go to some concerts of local musicians drawing primarily on the traditional musical culture. Unfortunately, it was hard for my husband’s family to find any events. They explained that there are not a lot of concerts in Lahore. The master musicians (ustad-s) play only a few times a year, and their concerts are expensive (like $200 a ticket!) and exclusive. After some searching we learned that on the night Farhan and I returned to Lahore from Islamabad, Cafe Peeru’s was hosting a “ghazal” night. Perfect, we thought! As it turned out, it wasn’t “perfect” in the way I had hoped, but still, there was plenty to see and hear.

In the following paragraphs I give some observations of the show. My training as a musician and a musicologist gives me a certain point of view that I am not trying to hide. At the same time, I am sure there are things I have missed or misunderstood. I would be curious to learn, especially from Pakistanis, how other readers respond to what I will say. Perhaps people can make comments at the end of my post or on Facebook.

The design and feel of Cafe Peeru’s is enjoyable, and I recommend it to anybody who hasn’t gone there yet. There are several wooden tables outside under a canopy of trees, with colorful fabrics and lanterns hanging from it. Even though the air was cold and we were sitting outside, a nearby fire sufficed to keep us warm.

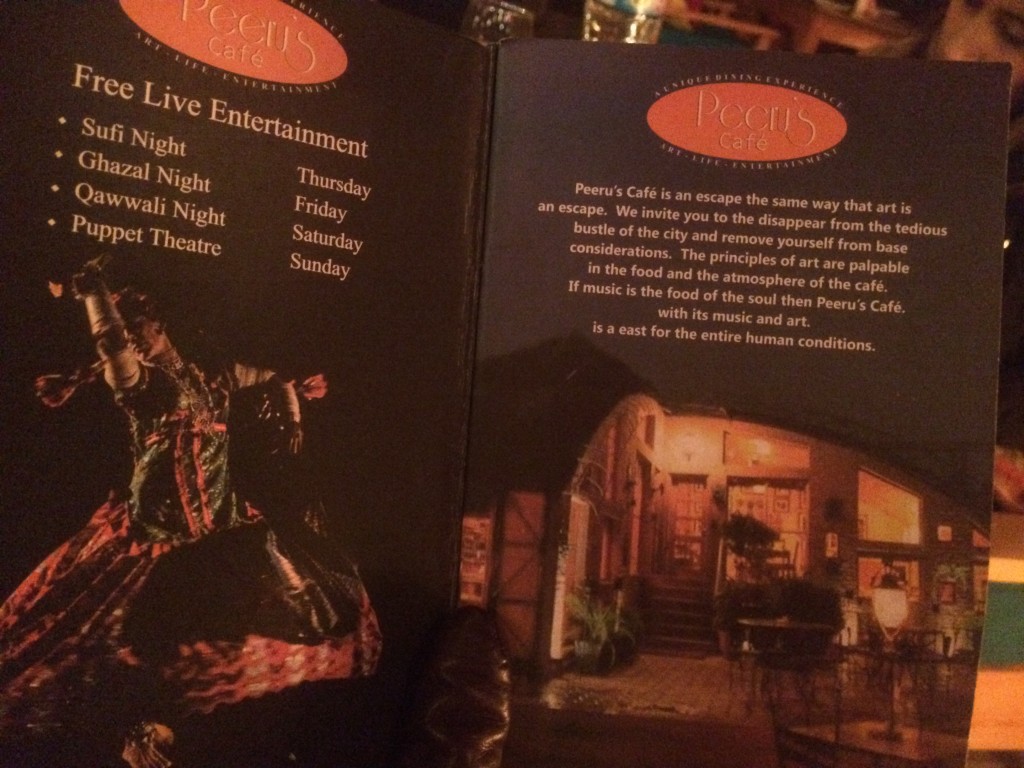

On the menu a vision for the cafe was explained:

Indeed this cafe was unique among all of the restaurants I visited in Lahore or Islamabad, because it clearly had been designed to do what the vision statement suggested, to serve as a kind of unique, beautiful, artful escape from mundane life.

My experience of the music at the cafe was hardly sublime but rather a kind of confused and disconnected cultural jumble. The confusion manifested itself in the band’s instruments, the style of the music, and the choice of songs. As shown in the above photograph, the musicians consisted of 1 male singer, 1 electric keyboard player, 1 electric guitar player, and 1 of those djembe-ish drums that seem to have become a percussion instrument of choice around the world over the last 25 years. (For those who don’t know, a djembe is a traditional drum from West Africa that is portable and can produce a variety of distinct sounds). I felt disappointed when I noticed these instruments on the stage upon entering, because I was hoping to see the more traditional harmonium and tabla drums. What I did see suggested some kind of world pop fusion. Not wanting to fall into the typical tourist mode of privileging one’s imagined idea of the traditional essence of a distant culture, I said to myself, ok, let’s see what they do with these instruments.

In contrast to the plain shirts and pants of the instrumentalists, the singer wore stylish, cosmopolitan clothes. Before they began he explained that they were aiming to do something in the style of Coke Studios. I have never researched Coke Studios thoroughly, but as I have been learning more about contemporary Pakistani and Indian music I have come across it several times. As far as I have observed, in a place like Pakistan where there is not much infrastructure to support music, Coke Studios steps in and offers the local musicians a performance platform that of course also doubles as advertisement. Generally, the musical results are a kind of “world music” in which the melodic content remains local but is inserted into a rhythmic, harmonic, and formal context that is firmly Anglophone rock. The example of “Allah Hu” by the Nooran sisters is a clear case of such a stylistic transformation. Originally a pretty traditional (I think) Qawwali song with an emphasis on mystical poetry that is meant to take listeners into a different state of consciousness, in this Coke Studios version most of the words have been cut out and what is left is a metrically regular, thickly-textured groove. Here is another extremely hodgepodged example I happened upon when I was looking for the traditional Istanbul song “Üsküdar’a Gider iken”. The transformation results in a seductive sound that people from all over the world can potentially nod their heads to while they are at work, stuck in traffic, or wait for their food to arrive at a restaurant.

In the case of our “ghazal” concert, this meant a local vocal style the likes of Shafqat Amaanat Ali with a regular rhythmic/harmonic grid. The guitar and keyboard players employed jazzy idioms built from tertian chords. The djembe player played with only two different hand strokes (trained tabla players can make many different sounds on their instrument) and he played something like a fusion of a rock beat and some tabla-like fills. The first song was an arrangement in the above-mentioned style of a “ghazal,” but then after that the band mostly played Bollywood hits. They only played ghazal tunes when Farhan’s family members went up to the stage and specifically requested them. The band wasn’t familiar with some of these requests. In terms of overt behavior, Farhan’s parents seemed to be the only people present in the audience who had considerable knowledge of the ghazal genre.

As is probably clear, I am not a fan of Coke Studios, but we have to recognize that there are reasons why musicians such as the Nooran Sisters have entered into business with it and why the guys at Cafe Peeru’s seemed to be trying to get in on it. That is, there is a benefit, a usefulness, a value being created in the Coke Studios institutional space. Apparently Nestle also sees the value, because in Pakistan the Nescafe Basement is also operating (some people might understand the contradiction between multi-national Nescafe and Basement, which in the U.S. refers to a very small, local venue). This is an example of globalization. I thought frequently during my time in Lahore about globalization, because it seemed to be staring me in the face much of the time. “What is it, exactly?” I wondered. My tentative and not so sophisticated answer is that it is fundamentally power flowing among geographically distant points. Several years ago I learned of the debate among humanities scholars about whether globalization was primarily helpful or harmful. It seems to me that it depends on the directions of the flow of power. In the cases of specific performances at Coke Studios or Nestle Basement, are the local musicians getting to use as much as they are being used? I don’t know, but I am not optimistic, because even if the performers featured in such media are reaping a lot of benefits, the mode of production is ultimately capitalistic. I believe a power flow operating under capitalist principles, if not carefully managed, can engender an extreme power imbalance. In this particular case, very profitable music can be produced that only requires the participation of a small number of workers (many of whom might be making low or no wages). The final product consists of mass-produced, mass-media forms that are infinitely replicable. Such an arrangement has the potential to put large numbers of local musicians out of work and to standardize or flatten out the music being produced.

Back to our band at Cafe Peeru’s. The vocalist and guitarist had attained a certain level of musicianship; what I mean is that they had enough technical ability and performing experience that they were attuned to each other, and it was pleasing to watch and listen to them relating to each other through the music. The keyboard player often sounded like he wasn’t fitting stylistically with the others. The djembe player had trouble relating to the vocalist, who was leading the ensemble. It seemed that he often just wasn’t listening, so that when the vocalist tried to soften the group’s sound he didn’t follow, and so the vocalist had to directly gesture to him to play with less energy. As some people might know, in the traditional musical culture of this region, musicians learn by observing and playing with older master musicians for several years. The result is that the disciples attain a deep familiarity with the performance practice, and so when you watch them perform together they are communicating with extreme sophistication in mostly non-verbal ways. This “ensemble problem,” as some musicians call it, was compounded that night in Lahore when a man in the audience who appeared to be the owner of Cafe Peeru’s started to also play on his djembe. The two percussionists were continually clashing. I think the owner wanted the younger djembe player on the stage to follow him as he played a more complex part, but this certainly wasn’t easy to do given that the older musician was not even visible to the other one, being concealed behind a table to the musicians’ right side.

To conclude the observations about the performers, I can say that the vocalist had a vision for the musical experience he was leading, just as the owners of Cafe Peeru’s aimed at a special experience in their restaurant. Will he be able to realize it? What will happen to this vision as he finds himself in particular institutional arrangements and gains more knowledge about his profession?

At the end of the post I would like to briefly describe the audience. Eventually the following groups were present: a young couple sitting right in front of the stage, the six of us sitting a little further back, and a large family of three generations behind us. On the left side there was the owner at a semi-private table by the stage, a group of 5 middle-aged men behind him, and then a group of 5 middle-aged women out celebrating someone’s birthday. Besides us, the djembe-wielding owner, and the large family, the people at the other tables did not visibly engage with the musicians in any way. Several times the singer explained that if the people liked the music they could clap to demonstrate it to the musicians, but for some reason, most of the audience seemed to do nothing at the end of each song. Actually, while I watched them, the majority of the people didn’t seem to be paying attention whatsoever to the music.

The large family spread over a few tables at the back of the space at first acted excited about the music. The patriarch had his children go up and request not one but two Bollywood hits in dedication to his wife. Besides us, this family were the only other people to request songs. Both times when the musicians started the requested song the family behaved in a marked way, recording the performance and taking pictures with phones, laughing and speaking excitedly about what was happening. But, after less than a minute these behaviors stopped. After maybe 20 minutes of this extreme high-and-then-low pattern of reaction, the family became subdued and, looking tired or unhappy, they left.

At least in terms of observable behavior, the singer’s repeated attempts to engage with the audience were almost wholly lacking in reciprocity. This, frankly, made me sad, because in traditional Pakistani and Indian music the musician-audience exchange can be incredibly rich. That is, somewhere in Pakistani culture the potential for such a musical experience is there, I am sure of it, but the knowledge required for it is perhaps not diffusing through society. I asked Farhan about why the audience was behaving in such a way at Cafe Peeru’s. He pointed out that he himself had never gone to any concerts in Pakistan before we went to this cafe, and that in all of his many years of education at a variety of schools in Karachi and Lahore, he never learned about music. People like me who were enculturated in (i.e. grew up in) cultures featuring frequent presentational musical experiences (i.e. concerts, talent shows, recitals, school choir shows) can come to believe that knowing how to attend a concert of a certain kind of music is natural. Actually, though, we have to learn how to do this. As evidence, just think of people you have witnessed clapping at the “wrong times” in concerts of European art music.

I have a few more (and more positive) experiences of music in Lahore to share with all of you, but I will save them for the next post.