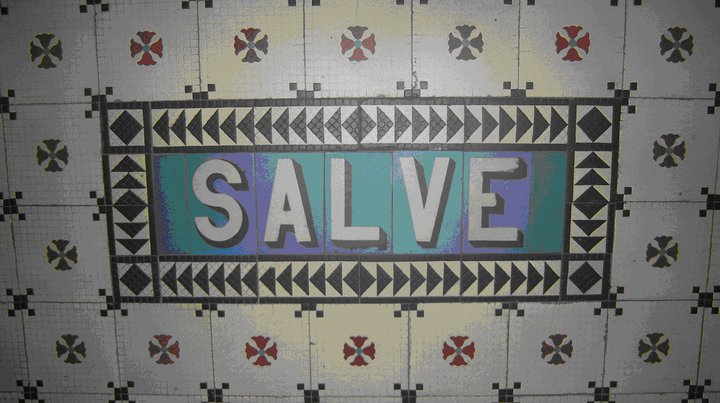

In 2010 I saw this mosaic of the Latin term salve, a once common greeting, at the entrance of a church building in Paris. (I’m sorry, I can’t remember which church!)

Why are Ph.D.s and medical doctors all called doctors? My interest was peaked in this question when I kept seeing the word docte being used as an adjective in the French translation of The Name of the Rose by Umberto Eco. Then one thought tumbled into another and, well, here it all is.

This blog post jumps off from the mystery of the origin of the word “doctor”. From this general etymological history I will then move to with increasing specification to a consideration of the profession of musicologist as a kind of doctor.

By doing just a bit of research on the cool site etymonline.com and having conversations with a few friends, I have formulated some ideas about this word that I think are worth sharing. Its root is old, this word “doctor.” The English term doctor originates from the Latin docere, which came to refer to someone who executed the verb “to teach”. Going back further in history, this Latin term meant “make to appear right,” and so its etymological link to the word decent becomes evident. And if we take docere back and further back, 4,000 to 6,000 years ago and well past the innovations of medicine and universities, we find that according to linguistic historians, “doctor” traces a line of descent from a Proto Indo European word-stem that is common to Greek, Sanskrit, Latin, French, English, German, and many other later languages. This stem is dek, which can mean: to take, to accept, greet, be suitable. In Greek this stem evolved into the word dokein: to appear, seem, think.

The meaning of dek is significant: essential to all of the definitions listed directly above (to take, to accept, greet, be suitable) is that the entity acting out the verb does so in confrontation with some other entity. A second thing that the first thing responds to, based on what it believes to be the nature of the second thing, by accepting it, taking it, greeting it, becoming suitable to it. There is something like a generative hierarchy in play, where there is a zeroth-order or initial event and then a first-order event that cannot occur until after the zeroth-order event. The collection of verbs related to the dek stem address the first-order event, the seer who registers or witnesses what is appearing. For reasons that I hope will become clear in the following paragraphs, I find the etymological origins of doctor leading back to dek to be a beautifully apt definition of what both medical doctors and academic doctors essentially do.

How apt that at the start of his narrative about the life of Jesus, it was a trained doctor, Luke, who describes his methodology in terms of eyewitnesses and careful investigation. It is not my intention here to make any claims about the absolute truth of any kind of religion or science. My intention is a consideration of the meaning of words and how they relate to my life experiences. But, isn’t it interesting that many religions give a central place to the practice of witnessing, or testifying, and that we find the same emphasis in the central practices of medical doctors and academics? I realize that for some people this term might have a religious tinge; I am neither focusing on nor neglecting that tinge, but rather, I want to examine the term with an even broader view.

A doctor understood as a master seer, whether they be of the medical or the academic variety (or both) must be always sensitive to the limited position embedded in the term commonly used to describe their professional station. The term doctor as a proper verb agent cannot apply if the agent has transgressed the balance. As we have seen above, the doctor is in a kind of second position (the first-order position) to phenomena that occupies a kind of ordinally superior position (the zeroth-order position). This initial thing occurs and then the doctor responds by trying to perceive it, requiring any good doctor to start their task with the invaluable act of witnessing. It follows that a preponderant part of the education of any kind of doctor must address the ability to witness: both making more precise the tools that record the impression and developing the doctor’s interpretive skill at determining which impressions are most “real” and which are problematic enough to be discarded as “false.”

Think about what, ideally, makes modern doctors superior to other kinds of people who might be able to “cure” illnesses. Doctors not only observe symptoms, they try to observe the cause of all of the unpleasant or unusual things the patient is experiencing. Doctors, with the aids of modern scientific knowledge and technology, not only prescribe medicine to stop someone from experiencing headaches. They can find the cause of those headaches, such as a cancerous tumor in the brain. Furthermore, doctors have some knowledge of the biological processes that cause cancerous growths, which is generally the out-of-control growth of cells. And at least in part, doctors have some idea of the different possible causes for that out-of-control growth. We can summarize the station, therefore, of a doctor as yes, someone who cures or finds solutions to fix bodily problems. But the first step in treating the bodily problem is seeing or witnessing that problem, and in optimal conditions all the way to the problem’s fundamental aspects. A doctor might not be able to do much to cure an advanced, fatal disease, but it’s still valuable in some measure just to be given the knowledge of the material/bodily origins of one’s suffering. Patients often cannot, by examining their own body, come to this kind of understanding. It’s a sad thing that many people currently experience doctor’s appointments in which the doctor will only prescribe medicine to treat symptoms and doesn’t seem to have the time to talk to the patient about their root causes and the corresponding, truly healing solutions.

At a certain point in my advanced musicology education, I found that my most significant progress consisted in learning about the extent of what I did not know. In my first year of musicology course work I felt fairly comfortable judging the value of a certain song, or musical culture, or performance to be poor, even if I had no real sensory experience of how it felt, sounded, or looked. Indeed, I took up this educational path to learn more about the music that I “loved”, and for a time this love blinded my capacity to know. It’s clear to many of us, I think, that such strongly pronounced yet weakly supported judgments were not ethically sound. A musicologist is someone who is supposed to communicate knowledge about music, which is an intimidatingly gigantic field of knowledge, due to its cultural and individual diversity. Because one can only pass along knowledge they already have access to, if I am asked about something (musical or otherwise) of which I am ignorant (lacking knowledge), I try not to erroneously skip the knowing process and pretend to be in a position to make some kind of value judgment. By the end of my second year of education at the University of Maryland, I had grown more inquisitive and also less inclined to drop the hammer of authoritative aesthetic judgment. It was a big change for me, and I have my professors at that institution to thank, in particular my Introduction to Ethnomusicology professor Robert Provine. Truly, he played a major role in opening my ears, eyes, and mind to music.

Now I find myself working as a musicology professor. It’s a dream come true—a dream that came true after 23 semesters of university coursework in music. Slowly I collected more substantive knowledge about the history of musics around the world, I had many invaluable, first-hand experiences of musical phenomena that I remembered and reflected upon, and I learned so much about my lack of knowledge and how to deal with my limits. Instead of the feeling of “Aha, I know about that!” I now feel more often battle with feelings of skepticism and fears of inadequacy, despite which I still need to act out the tasks of my profession competently. I find myself asking, “Am I sure about X or Y fact that I have inserted into this presentation?” “How else do I need to extend or deepen my research before I can confidently write an article about this research project?” And often when people ask me questions about music, I feel compelled to start by acknowledging clearly the limits of what I can reasonably say. When I catch myself speaking out of ignorance, as I can still slip into doing, the wisdom of my education about knowledge and ignorance speaks up to convict me.

In contrast to all of these negative statements, what then, do I consider my job as a musicologist to be? As is already clear, it’s certainly not to know everything about music, which I have learned is impossible. And it’s not primarily to give opinions about good and bad music, although I do consider that to be a useful part of my vocation in certain situations. Rather, it’s to try to serve as a witness to musical phenomena: to be present when music occurs. I can do that through the written descriptions of other people, but it is especially important that I am present to observe music when it happens, if not live then at least through high quality media recordings. In so far as I am able to observe anything, I try to strive for relative accuracy. To see/hear/feel what I can palpably perceive with my senses and to at the same time be aware of both the limitations of my senses and the limits of the information that has come through them. In a word, to be authentically empirical, whether I am out purposefully conducting my research or I find myself in the midst of musical experience in a more informal way. This might sound like an easy task, but I haven’t mentioned all of the possible pitfalls, and it is easy to start chasing after something that isn’t there. For all of my research and formal (classroom) as well as informal teaching, the heuristic (general concept) of “witnessing” is quite helpful for me. I am trying to serve as a witness, to recognize the difference between witnessing something and fantasizing or gossiping about it, to be able to evaluate the works of other scholars as trustworthy testimony or not. I have, for example, tried to take such a posture in the blog posts that I wrote about what I witnessed firsthand about the cultural life of Lahore, Pakistan (Part 1, Part 2, Part 3, Part 4, Part 5).

As I am writing this there is a thunderstorm outside, which reminds me of a childhood memory that seems pertinent here. When I was a kid and the National Weather Service called a tornado warning for our county, my parents would go outside and gaze intently at the skyline for signs in the forms of the clouds that a tornado was coming, while I would call desperately to them to hide with me in the basement, terrorized by the tornados whirling in my imagination.

As the tumble of my thoughts seems to have come to its end, it might be useful to re-connect the end to the beginning, that definition of dek as “to take, to accept, greet, be suitable.” How instructive is the progress suggested across the four terms of the definition, starting with the basic registering of the music right in front of me, and moving more and more towards a position of greater familiarity with it, so that the verb becomes more and more active, passing from acceptance, to actively uttering with my body some kind of greeting (hence the “Salve” picture I placed at the top of this post). At the end of the chain, the process progresses to an action state where now perhaps what I have acknowledged might result in a kind of change in me, as I become suitable to it. Or perhaps I will decide at that point that the thing I have learned about does not personally suit me, suggesting that this is the moment at which a limited judgment towards what has been observed is a valid possible action. We don’t tend to refer to musicians as doctors, but the progress in the definition of dek also seems applicable to a music lesson, where the student first understands what the teacher is doing and then imitates it. The start is relatively more passive while the end is much more active, and any good music student knows that you must pay close attention when your teacher is showing you something. The same could be said for many other forms of education, of course. It seems that only at the final stage, where the cumulative aspects of the activity of knowing culminate in a kind of transference from the zeroth-order entity to the first-order entity, like an electrical charge that jolts the mere seer into a more active state of becoming suitable to what is seen, can there emerge one who is rightfully qualified to teach.

This blog post has mostly involved asking questions and formulating general answers. In a few subsequent posts I will talk in more detail about some epistemological issues that I try to address in my research and teaching.